By Kristina Lucenko

Patience Boston was an Indigenous woman executed in 1735 in York, Maine, for the murder of her English slaveowner’s grandson. Public executions like Boston’s were extremely popular and well attended during the English colonial period. They often produced a range of “gallows literature” assembled and printed by New England clergy, including sermons, narratives, last words, and dying warnings. These writings focused on the spiritual transformation of the criminal awaiting execution rather than on the crime itself.1 The published narrative of Patience’s life reveals not only a tumultuous and short life, but also her own awareness of the structures of colonialism and racism that she fought against.

Patience Samson was born on December 26, 1711, in Monomoy, Massachusetts, one of seven communities of Christianized Wampanoags on Cape Cod.2 Her parents, John Samson and Sarah Jethro, seem to have been from high-ranking families. Her mother was in “full Communion” with the Christian Indian congregation of the nearby town of Nauset, and had Patience baptized as an infant.3 Patience was only three years old when her mother died, at which time she was “bound out” to an English family named Crowell (or Crowe) with whom she stayed until she finished her term at the age of eighteen. A year or so later, Patience married a man named Boston, an enslaved African with whom she had two children who both died as infants. As a condition of marrying Boston, Patience became enslaved for life to Boston’s master, Elisha Thatcher (at Thatcher’s insistence). She later stated that “because [Boston’s] Master would have it so, I bound my self a Servant with him during his Life Time, or as long as we both should live,”4 enacting what seems to be framed as a “spousal,” or common-law marriage, through a “perverse echo of the marriage vow.”5

Her enslavement to Thatcher seemingly weighed heavily on Patience, and her life demonstrated a deep struggle with her circumstances. As later described in her narrative, she and Boston quarreled frequently, she drank excessively and was sexually promiscuous, and she falsely admitted to having killed one of their children. After her acquittal and with her husband’s consent, Patience was bound to a relative of Thatcher’s, a “Capt Dimmick,” perhaps by her choice, as her confession later stated. A year later, she again “asked” to be sold, this time to Joseph Bailey in Casco Bay, Maine, some three hundred miles north of Cape Cod, so that she could be closer to another enslaved Indigenous woman with whom she was in community. Not long after, she was sold yet again by Bailey to Benjamin Skillens of Falmouth, Maine. Although her pattern of re-placement into different white households suggests instability and desperation, it also suggests that Patience exerted some control and agency over her movement, and that she sought and secured the company of Indigenous relations.

At around this time, Patience claims to have become pregnant again and then to have committed another act of infanticide (both of which were unproven). It is not difficult to imagine that the loss of her children was traumatic and tormenting; it is also not difficult to recognize what must have been intense fear, pain, and anger in understanding that any children she had would, in all likelihood, also be enslaved by white settlers.

Patience’s anger and her own grief soon led to a radical action: the murder of her enslaver’s grandson. Few details are given, but when she was arrested and imprisoned in July 1734, she was accused of dropping the eight-year-old Benjamin Trot into a well, where he died. On June 24, 1735, at the age of 23, Boston was found guilty and sentenced to death. She was hanged on the same day.

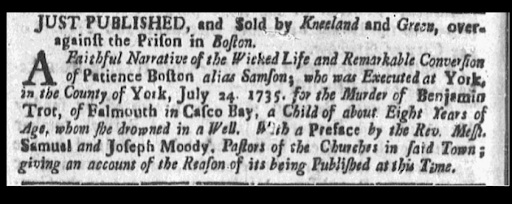

Not long after her execution, an 8-page pamphlet was published that mostly exhorted readers to not follow Boston’s sinful example.6 Three years later, in 1738, the narrative was expanded to include Boston’s first-person account of her life and conversion; it was assembled and prefaced by Reverend Samuel Moody and his son Joseph. Titled A faithful narrative of the wicked life and remarkable conversion of Patience Boston alias Samson, it was published in Boston in 1738. Criminal conversion narratives such as this presented first-person accounts of the convicted murderers’ lives and were framed by ministers as glorious stories of God’s saving grace.

What is remarkable about Boston’s narrative is that she was able to communicate her own message. Her narrative reveals how white supremacy in New England disrupted and colonized Indigenous family relations and created conditions for long-term involuntary servitude and enslavement.7 Transcribed, assembled, and printed by father and son Puritan ministers Samuel and Joseph Moody, Boston’s narrative reveals an awareness—both Boston’s and the ministers’—of white dominance in the context of English colonization. As such, the text provides insights into Boston’s personal experience and feelings around involuntary servitude and forced acculturation that were not part of the ministers’ intended framework. The story of Patience Boston and her life in early New England serves as a record of the use she makes of Christianity in protecting some of her agency as a Native woman in a white-dominated society.

Toward the end of Boston’s narrative, the word “frame” is evoked several times to indicate a mental and emotional state of agitation and unrest. She mentions “dreadful risings of Heart against God’s Decrees concerning the Children of Men, and his Disposing of them, according to his mere Will and Pleasure” specifically regarding pleading not guilty at her trial so that she and her child could return to their community.8 She characterizes these thoughts as belonging to a “wicked,” “dark,” “evil,” and “bad” frame lasting about ten days.9 Later she states: “sometimes it seems to me that I could speak and hear of the Things of Christ Day and Night without Weariness. But I am not always in such a Frame.”10 In these statements, Boston seems to describe the ambivalent ideological position of the Indigenous person within a white settler social structure. Through some processes (such as Christianization), such a person is formulated as having the capacity for change and improvement, and through others (such as enslavement), they are seen as unable to change and become “civilized.”

More than simply expressing a struggle with God’s authority and rules, Boston here recognizes her position, and that of the white settler, within the colonial system. Boston’s narrative also reveals how the developing colonial regime’s twin goals of racial discrimination and moral reform are reflected in concerns over Indigenous women’s reproduction, and specifically their capacities as mothers and domestic servants.

Further Reading

Grandjean, Katherine. “‘Our Fellow-Creatures & our Fellow-Christians’: Race and Religion in Eighteenth Century Narratives of Indian Crime.” American Quarterly, vol 62, no. 4 (December 2010): 925–950.

Newell, Margaret Ellen. Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and The Origins of American Slavery. Cornell University Press, 2015.

Newell, Margaret Ellen. “In the Borderlands of Race and Freedom (and Genre): Embedded Indian and African Slave Testimony in Eighteenth-Century New England” in Hearing Enslaved Voices: African and Indian Slave Testimony in British and French America, 1700-1848, ed. Sophie White and Trevor Burnard (Routledge, 2020), 98–118.

Footnotes

- The classic studies of the genre are Daniel Cohen, Pillars of Salt, Monuments of Grace: New England Crime Literature and the Origins of American Popular Culture, 1674-1860 (Oxford University Press, 1993); Karen Halttunen, Murder Most Foul: The Killer and the American Gothic Imagination (Harvard University Press, 1998); and Daniel E. Williams, ed., Pillars of Salt: An Anthology of Early American Criminal Narratives. (Madison House, 1993).[↩]

- Boston was born in Monomoy, a village within the Wampanoag Nation; however, being born in Monomoy does not mean that Boston’s tribal identity was Monomoyick (personal correspondence with Dr. Nitana Hicks Greendeer). Thus in this entry I do not ascribe to Boston a tribal identity that I am unable to confirm. For many biographical details of Patience Boston’s life, I have gratefully relied on Frances Herman Lord’s richly researched and contextualized study of Boston, which remains an indispensable source for details of her life and the lives of the white settlers who enslaved her. See Lord’s Patience Boston, Indian Woman: Social Deviance, Conversion, and Redemption in Early Eighteenth Century New England, M.A Thesis, University of New Hampshire, May 1991.[↩]

- Boston, Patience, A faithful narrative of the wicked life and remarkable conversion of Patience Boston… (S. Kneeland and T. Green, 1738), 1.[↩]

- Boston, A faithful narrative, 3.[↩]

- Newell,Margaret Ellen. “In the Borderlands of Race and Freedom” 104. Ann Marie Plane argues that the English tradition of spousals, or informal self-marriages, were “quite frequent, if not the norm,” among enslaved Natives and Africans in colonial New England (136). She also points to the contingency of these unions between enslaved people in the eyes of their white masters, noting Reverend Samuel Phillips’ stipulation that enslaved couples were married “so far as shall be consistent with the Relation which you now sustain, as a Servant” (qtd. in Plane, 139). In other words, the terms of the marriage were only legitimate within the context of enslavement, and at any point either enslaved person could be dispersed through sale or bequest, thus dissolving the marriage. Colonial Intimacies: Indian Marriage in Early New England. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2000.[↩]

- The confession, declaration, dying warning and advice of Patience Sampson, alias Patience Boston… London: 1735.[↩]

- Rebecca Goetz notes that scholars who use the phrases “Indian slavery” or “Indian enslavement” refer to a wide range of experiences and practices that vary across regions and over time. Although defining slavery is a complicated and contested endeavor, “the word serves as a way of thinking about people who were under the power of others against their wills for a variety of purposes, including but not limited to labor” (61). See “Indian Slavery: An Atlantic and Hemispheric Problem,” History Compass 14/2 (2016): 59–70, 10.1111/hic3.12298.[↩]

- Boston, A faithful narrative, 24.[↩]

- Boston, A faithful narrative, 25.[↩]

- Boston, A faithful narrative, 28.[↩]