By Annabel Richards

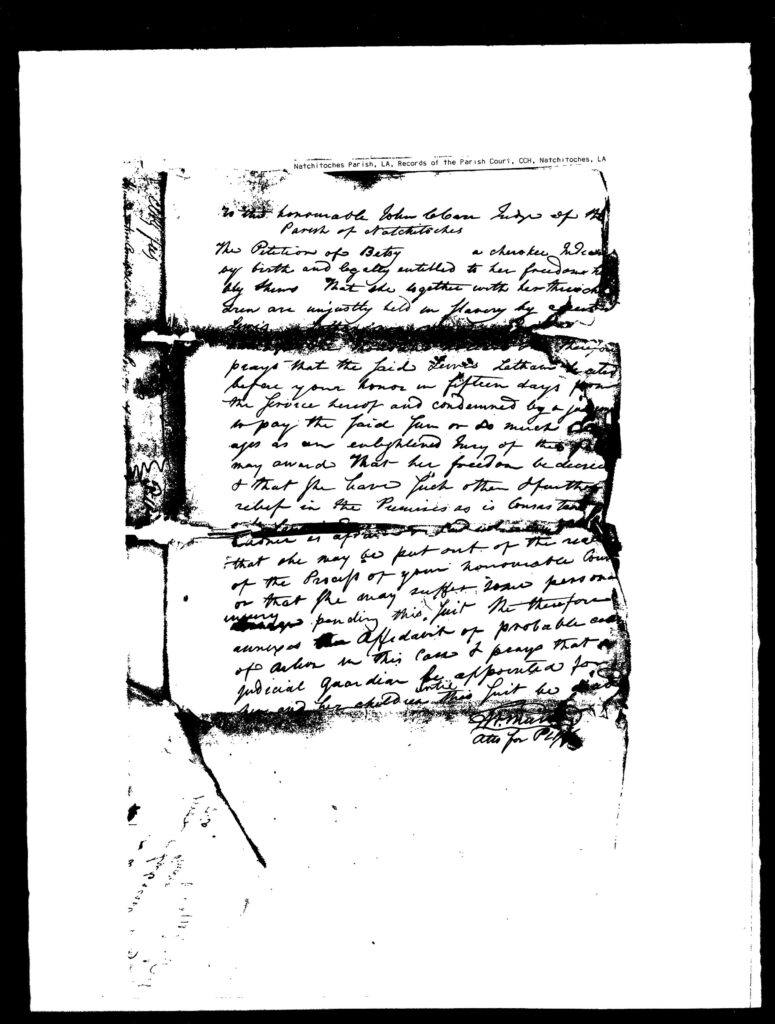

In the year 1812, a thirty-five-year old mixed-race Cherokee and Black woman named Betsy bravely petitioned for the emancipation of herself and her three children from the illegal enslavement of one Lewis Latham, who had purchased her the year before. In her testimony, she attested that she was the daughter of a free Cherokee woman, making her enslavement illegal given the laws of Louisiana at the time. As part of her petition, she asked that $1,000 be paid to her as compensation. Betsy, fearing for the safety of herself and her children, also requested that she be granted a guardian for the duration of the trial.

Betsy’s claim to freedom prompted a detailed process as state officials tried to understand her background and lineage. As was often the case in such circumstances, the first step was almost always to find witnesses and even relatives who could testify under oath about family information and where the individuals petitioning for their freedom had come from. This sometimes led to contradictory evidence, especially regarding enslavement status and racial definitions. Proving one’s freedom in court was a dangerous, challenging business.

Many of the files for Betsy’s case have been lost or damaged, leaving many details out, but certain things can be learned from the surviving files. It seems Betsy was born around the year 1777, during the American Revolution, likely on traditional Cherokee lands in what is now North Carolina, Tennessee, or Georgia. Although the records are silent on how she came to be enslaved, it is possible that she was stolen by American soldiers during the Revolution. By the early nineteenth century, she had been trafficked westward to Missouri, and purchased by Richard Crawford and his wife at either St. Michael or Cape Girardeau. Afterward, a witness in the case named Daniel McNeil testified that he remembered seeing Betsy with the Crawfords along the St. Francis River, south of St. Louis. The Crawfords eventually took Betsy and her children to New Orleans in 1810, where the Crawfords sold them to Lewis Latham in 1811. A year later, Betsy sued for her and her children’s freedom.

Witnesses called before the court could not provide definitive proof of Betsy’s identity or status, at least by their definitions, and Betsy’s own testimony was not enough to free her. Two witnesses named Mary and Daniel McNeil both claimed that Betsy was enslaved and was recognized by other people as such. And yet on March 25, 1812, a man named John L. Pettit swore an affidavit that Betsy was free. It is unclear how he knew Betsy, but he may have been put at some risk by this action, too. Neither of the McNeils knew the identity of Betsy’s mother or provided any other information about her life, despite Mary claiming that she knew Betsy “very well.” Betsy was interchangeably described as “Indian,” “Cherokee,” “Black,” and a “Mulatresse,” reflecting the common prejudice that Indigenous people faced by enslavers who wished to downplay their Native family lineage (thereby increasing their enslavability).

Betsy’s case unfolded during the period in which Louisiana Territory was petitioning for statehood. Previously under Spanish Louisianan rule, it had been illegal for Indigenous people to be enslaved, but the law was unevenly enforced. Such lack of clarity continued under American rule.2 In 1811, Louisiana saw the largest slave revolt in American history, with five hundred enslaved people rioting and leaving two white men dead.3 These events likely colonists’ heightened the fear of enslaved people as well as the fear of their emancipation.

Betsy’s case dragged on for two years before it was dismissed in 1814, leaving her and her three children still enslaved. It is unknown what became of them after they were returned to the Latham household. Were they punished for their claims to freedom? We can’t be sure, but such retaliation sometimes happened to other unsuccessful claimants. Betsy’s case illustrates the challenges enslaved Natives faced when suing for their freedom. Their memory lives on in the pages of these documents.

For further reading

Gross, Ariela Julie. “Legal Transplants: Slavery and the Civil Law in Louisiana.” USC Law and Legal Studies Paper no. 09–16 (2009): 1–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1403422

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press, 1995.

Fessenden, Marissa. “How a Nearly Successful Slave Revolt Was Intentionally Lost to History.” Smithsonian Magazine. Jan 8, 2016. www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/its-anniversary-1811-louisiana-slave-revolt-180957760/

Footnotes

- “To the honourable John C Carr Judge of the Parish of Natchitoches,” Slavery and the Law Archive, https://congressional.proquest.com/histvault?q=101693-001-0135&accountid=9758[↩]

- Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo, Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 336.[↩]

- Fessenden, Marissa, “How a Nearly Successful Slave Revolt Was Intentionally Lost to History,” Smithsonian Magazine, Jan. 8 2016, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/its-anniversary-1811-louisiana-slave-revolt-180957760/[↩]