By Courtney Akbar (Hassanamisco Nipmuc)

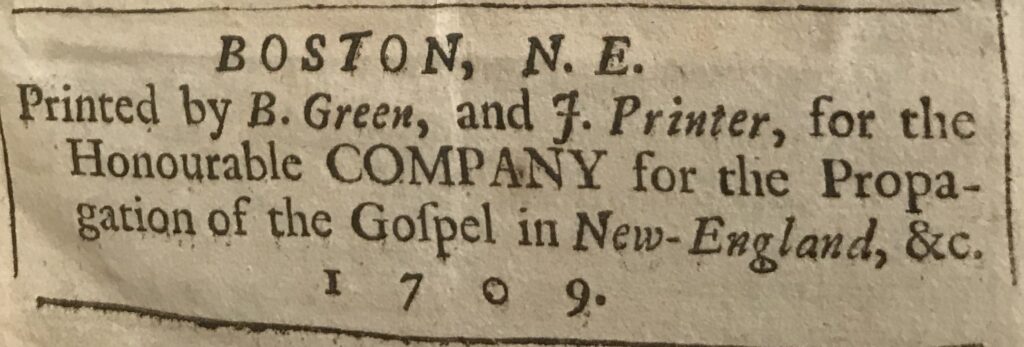

The Massachusett Psalter that was published in 1709. Credit to Wawaus for his

printed works appears only once in print as shown, “J. Printer.”1

Wawaus, alias “James-the-Printer” later shortened to “James Printer,” was an influential seventeenth-century Nipmuc leader who is most known today for his integral work translating and typesetting the first Bible printed in the Americas in 1663. He was the son of a prominent family; Naoas was his father, and notably, despite the Nipmuc being a matriarchal society, the name of Wawaus’s mother remained unrecorded.2 Wawaus was born around 1640 in the Nipmuc village of Hassanamesit (present day Grafton, Massachusetts), and by adulthood he was an intelligent scholar, linguist, printer, and eventually, community leader. During this transformative century, he observed the beginning of a wide range of colonization and genocide, from physical to biological to cultural, on his person, community, and livelihood, inflicted directly by the newly settled invaders.3

By the age of six, Wawaus was already living with an English family, as were other Native children throughout the region. Although not all Native children who were living with English colonists were there by choice, in some cases it was a diplomatic decision on the part of Native leaders. For the Nipmuc and other nations, it was tradition to send children to live with a neighboring nation, where the child would learn the culture and ways of the other community and then bring that knowledge back to their own community. These children would grow up to be loyal to both communities, and become interpreters and mediators in intertribal relations. Unbeknownst to the local Indigenous communities however, English customs were very different, and their approach to educating included corporal punishment and isolation of children as standard practices. These methods were most likely horrifying for Wawaus and his Indigenous peers, as in their culture children were not physically punished, being “..the most humored, cockered, indulged things in the world.”4 The English had their own motivations for taking in Indigenous children. Aside from converting Indigenous people to Christianity, they wanted title to the land and to convert the Indigenous nations as tributaries to the king of England. One way to do that was through the children.5

In 1656, Wawaus, along with one of his brothers, Job Kattenanit, and several other Indigenous children from neighboring tribes, entered Daniel Weld’s preparatory school on Crooked Lane in Roxbury, Massachusetts. At the one-room school (which exists today as the Roxbury Latin School) Wawaus and his classmates learned to read and write in English, Latin, Greek and Algonquian. They also learned arithmetic skills and to comport themselves according to English ideologies. In 1659, while some of his classmates continued on to Harvard College, Wawaus was “put to apprentice” under his “master” Samuel Green as a “printer’s devil,” which was a technical term for a person, typically a young boy, serving at or below the level of apprentice in a printing establishment.6 Wawaus’s days were spent at the Harvard Indian College with a few fellow Indigenous collaborators, performing arduous work for long hours, working on two presses for twelve to thirteen hours a day, printing one sheet at a time after setting out each individual piece of type by hand.7 Wawaus was invaluable to the printing process. Without his dual fluency and mastery of the art of typesetting, “the process would have been maddeningly slow and ‘grossly inefficient.’”8 By 1663, the entire Bible was published along with other various works of bilingual literature.9

Before the start of the War for New England (or King Philip’s War, 1675–1677), Wawaus returned home to his family for the arrival of one of his nephews.10 In June of 1675, with tensions between many Indigenous communities and the English at their breaking point, a meeting was held at Hassanamesit where the community declared to Massachusetts military personnel that they would not assist King Philip (Metacomet) in conflict. They were not asked to provide their assistance to the English at this time.11 On August 30, Wawaus was with his family at Okommakamesit (another praying plantation 12 miles from Hassanamesit) when Samuel Mosely, a settler and militiaman who had a reputation for barbaric brutality and cruelty (such as having captives torn to pieces by dogs), forced his way into their home and dragged Wawaus and his kin out at gunpoint. Wawaus along with ten of his family members had their arms shackled behind their backs and were tied together neck to neck with rope. Mosely and his men rode horseback while literally dragging James and his kin for thirty miles to a jail in Cambridge.12

At the same time Wawaus was taken captive, the Massachusetts Council issued an order declaring that all Indians “be confined to their several Plantations.”13 This order stated that they must crowd all of their wigwams (houses) into one part of their plantation, and that no one would be allowed to travel more than one mile from the “center” of those houses without the escort of an Englishman. Any Native person who was found outside of these strict imposed limits would “lose their lives, or be otherwise damnified” and “their blood or other damage (by them sustained) will be upon their own heads.” These limits severely impacted their ability to obtain food, water, tend to their livestock, and perform other necessary duties needed to survive. Nearby in Connecticut, a similar resolution was passed where any Indigenous person traveling alone could lawfully be “shot at will.”14 The Massachusetts General Court also enacted a law entitled “Indians Prohibited Being in Boston” four months later, which banned any Native person from entering the city of Boston “until application be first made to the Governour, or Council if sitting, and then to be admitted with a Guard of two Musqueteers, and to be remanded back with the same guard,” and “That it shall be lawful for any person finding any Indian in Town without said Guard to Apprehend and Secure him.”15 Egregiously, this Act was not repealed until 2005.16

Wawaus and his kin were imprisoned until late September 1675, being falsely accused of participating in a raid in the town of Lancaster. During his imprisonment, many fights broke out amongst the local settlers demanding the execution of Wawaus and the men with him without a trial. At his home in Hassanamesit, Massachusetts forces “destroy[ed] much of the corn and burn[ed] the wigwams.”17 Despite the English missionary John Eliot pleading to his fellow magistrates for their innocence, it was only because of the vocal defense of the Commonwealths’ Mohegan delegation that Wawaus and his relatives were finally allowed to stand trial. The court declared two of the men guilty, and released Wawaus and the others into the hands of Waban, the English-appointed leader of the Indigenous community in Natick. With the increasing amount of volatile laws against the entire Indigenous population, their ability to survive became increasingly unclear.

That November, a group of hundreds of Nipmucs arrived at Hassanamesit asking the families there to come with them to safety in Menimesit. They came with a foreboding warning. Just days before, an order had been passed and the entire community of “Praying Indians” at Natick had been abducted by the English in the middle of the night, with no more than a half-hour notice, bound in chains and rope like criminals, just as Wawaus had been three months prior. They were “disposed of to Deer Island.” The Nipmucs warned those at Hassanamesit that the English would “force you all to some Island as the Natick Indians are, where you will be in danger and starved with cold and hunger, and most probably in the end be all sent out of the country for slaves.”18 Whether Wawaus and his community left voluntarily, fearing displacement by the English, or if they were “carried away captive,” as Massachusetts magistrate Daniel Gookin later described, has been lost to history. By the end of that year, the Ponkapoag and Nashoba communities, as well as Wawaus’s brother Job, with his wife, children and other kin, had all been captured by the English in the same fashion and were forced into exile on the barren Deer Island.

The large community at Menimesit housed thousands of people who all shared an abundance of resources. In the early winter months of 1676, raiding parties from Menimesit destroyed entire English towns. Wawaus became a key figure in these raids, leaving at least two written messages to the Massachusetts authorities after setting fires to the ravaged English towns. He is credited with writing a notice posted “at the foot of the bridge which they fyred”: “Thou English man hath provoked us to anger & wrath & we care not though we have war with thee this 21 years for there are many of us 300 of which hath fought with thee at this time, we have nothing but our lives to loose but thou hast many fair houses cattell & much good things.”19 In this letter, it was made clear that it was the English who had started the war, a war that had been considered to have been ongoing for decades. Wawaus also is credited with writing another letter that negotiated and led to the release of the English captive, Mary Rowlandson, in May 1676.20 As the war went on, Wawaus was not only fighting against the English, but also his own relatives. His brother Job for example, had been allowed to leave Deer Island under the condition of serving as a spy for the English.

After the war was over, the retaliation by the English was merciless. Job, along with a few others, were able to “prove” themselves loyal to the English. The English proclaimed amnesty to all surrendering Natives, promising them “lives and liberty” even “to those that have been our enemies,” but the English did not stand by their own declarations. Those who came in under the guise of assured safety and protection were sentenced to death, forced to serve as scouts for the English, sent to the Caribbean as slaves, or divided amongst the English and bound to servitude (this was especially true for the children). Job and others petitioned for the lives of Wawaus and those who surrendered themselves and sought liberation, but unfortunately, their efforts only stalled the enslavement and death of many of them.

Wawaus ended up back at the printing press at the Indian College, where a second edition of the Indian Bible was printed in 1685. In a letter to Robert Boyle in 1683, Eliot wrote, “We have but one man viz. the Indian printer that is able to compose the sheets, and correct the press, with understanding.”21 Wawaus later took on the role of leader at Hassanamesit after his older brother and the previous leader, Annaweekin, had died. Wawaus lived until around 1709, spending his life advocating for his community and their lands. The final remaining parcel of Nipmuc lands at Wawaus’s home in Hassanamesit has never been out of the possession of the Nipmuc tribe. Today it remains a sacred meeting place where Wawaus is well remembered and revered by his descendants.

For further reading

“An Act Repealing the Act of 1675 Entitled ‘Indians Prohibited Being in Boston,’” May 20, 2005. Session Laws, Acts of 2005, Chapter 25. https://malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2005/Chapter25.

Brooks, Lisa. Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War. Yale University Press, 2018.

Drake, Samuel G. The book of the Indians of North America. Josiah Drake, 1833.

Fisher, Linford D. “America’s First Bible: Native Uses, Abuses, and Reuses of the Indian Bible of 1663,” in The Bible in American Life, ed. Philip Goff, Arthur Farnsley, and Peter Thuesen. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Fixico, Donald L. “When Native Americans Were Slaughtered in the Name of ‘Civilization,’” July 11, 2023. HISTORY. https://www.history.com/news/native-americans-genocide-united-states.

Hassanamisco Nipmuc Band Website.

Lepore, Jill. The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity. Knopf, 1998.

Morison, Samuel Eliot. Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century. Harvard University Press, 1936.

O’Brien, Jean M. Dispossession by degrees: Indian land and identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650-1790. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Peyer, Bernd. VThe Tutor’d Mind: Indian Missionary in Antebellum America. University of Massachusetts Press, 1997.

Temple, J. H. History of North Brookfield, Massachusetts. The town of North Brookfield, 1887.

Winship, George Parker, The Cambridge Press, 1638-1692: A Reexamination of the Evidence Concerning the Bay Psalm Book and the Eliot Indian Bible. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1945.

Yan, Xiaochen Sherry. “Untangling the Land History of Grafton, Massachusetts.” ArcGIS StoryMaps, May 11, 2022.

James the Printer – Cheryll Toney Holley

Genocide Of Indigenous Peoples – Holocaust Museum Houston

Footnotes

- “James the Printer,” image taken by Hassanamisco Nipmuc Sonksq, Cheryll Toney Holley, accessed Oct. 17, 2024, https://cherylltoneyholley.com/2023/05/06/james-the-printer/[↩]

- Lisa Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War (Yale University Press, 2018) 42. Much of this reconstruction is drawn from Brooks’ excellent book.[↩]

- When Native Americans Were Slaughtered in the Name of ‘Civilization’ | HISTORY; Genocide Of Indigenous Peoples, Holocaust Museum Houston.[↩]

- Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 84. [↩]

- Edward Ragan, “Colonial National Historical Park: A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown-The First Century (Chapter 6).”[↩]

- Joel Chandler Harris’s (Printer’s) Devil-ish Origins — The Wren’s Nest, printers devil, Oxford English Dictionary.[↩]

- Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 87; Morison, Samuel Eliot, Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century (Harvard University Press, 1936), 46, 349; Winship, George Parker, The Cambridge Press, 1638-1692: A Reexamination of the Evidence Concerning the Bay Psalm Book and the Eliot Indian Bible (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1945), 274.[↩]

- Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 87.[↩]

- Linford D. Fisher, “America’s First Bible: Native Uses, Abuses, and Reuses of the Indian Bible of 1663,” in The Bible in American Life, ed. Philip Goff, Arthur Farnsley, and Peter Thuesen. Oxford University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190468910.003.0002.[↩]

- Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 175.[↩]

- J. H. Temple, History of North Brookfield, Massachusetts (The town of North Brookfield, 1887), 74.; Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 176.[↩]

- Lepore, Jill, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity (Knopf, 1998), 299; James the Printer – Cheryll Toney Holley.[↩]

- Massachusetts History Timeline – History of Massachusetts Blog.[↩]

- Lepore, The Name of War, 299.[↩]

- “Several lavvs and orders made at the sessions of the General Court held at Boston the 13th of October 1675. As also at the sessions of Court held at Boston, the 3d. of Novemb. 1675.” And printed by their order, Edward Rawson secr. | Evans Early American Imprint Collection | University of Michigan Library Digital Collections.[↩]

- Session Law – Acts of 2005 Chapter 25.[↩]

- Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 207.[↩]

- Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 226; Gookin, “Historical Account,” 476.[↩]

- Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 258.[↩]

- Bernd Peyer, The Tutor’d Mind: Indian Missionary-Writers in Antebellum America (University of Massachusetts Press, 1997), 46.[↩]

- Drake, Samuel Gardner, Biography and History of the Indians of North America (B.B. Mussey, 1848), 51.[↩]