By Marjia Blašković and Adnan Aldabbagh

1n 1637, a Pequot captive boy was sent by John Winthrop in Boston to the home of Roger Williams in Providence, Rhode Island. Winthrop had renamed him “Will,” likely after his newly claimed master, Roger Williams. Will, whose Pequot name was once known, arrived in Williams’ household as part of a genocidal war against the powerful Pequot nation, one that Williams had directly enabled through negotiating Mohegan and Narragansett assistance. Will’s enslavement was part of the first major burst of Native slavery in New England as a result of what became called the Pequot War (1636–1637).

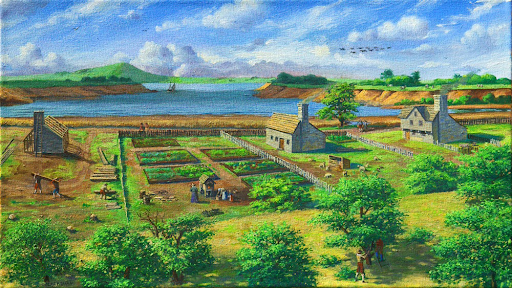

This conflict was caused by the expansion of English colonists to the interior, into the homelands of the Pequot, in what is now eastern Connecticut. Pequot resistance to this expansion led to tensions and eventually the murders of two traders. English authorities blamed the Pequot for both of the murders and declared war, determined to wipe out the Pequot nation. After an initial attack on the Manisee of Block Island (who were accused of allying with the Pequot), the English forces turned their focus on the Pequot homelands, destroying food stores and villages.

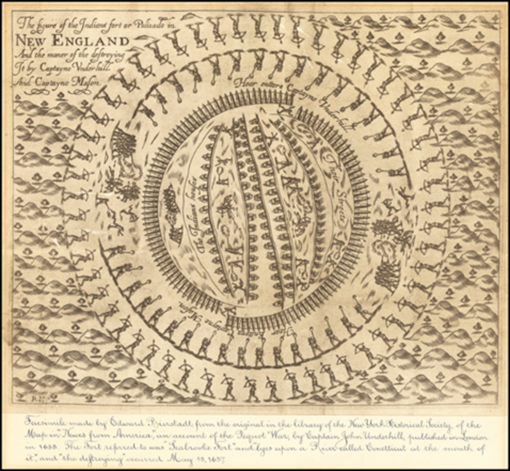

Frustrated with Pequot elusiveness, the English army planned an attack on a primary Pequot fort at Mystic, in what is now southeastern Connecticut. In the early hours of May 26, 1637, the allied forces of the English, Mohegan, and Narragansett struck the Pequot fort. After entering the palisades area, they set fire to the dozens of Pequot wetus, or domed houses, burning to death hundreds of Pequot women and children.1 The few who miraculously managed to survive the massacre decided to retreat from the region, but not all were able to find a lasting refuge.2

English forces continued to hunt down Pequots, chasing them westward through swamps and forests. When English soldiers had enough Pequot captives loaded into ships–usually women and children–they would send them to Boston, where they were sold as slaves.

In June some fifty Pequot women and children were shipped from the coast of Connecticut to Boston to be sold into servitude and slavery, and English commanders were quick to claim some of them.3 This included Roger Williams, who seemingly met the ship as it stopped in the Narragansett Bay en route to Boston. In a letter dated June 30, 1637, Williams asks John Winthrop, the Governor of Massachusetts Bay, to send him one of the boys who had caught his eye.4 Brief descriptions of other captives in the letter confirm how Indigenous people were judged and selected solely based on their bodies. In the case of this Pequot boy, Williams identifies him as having “the red about his neck.” It is unclear if that was a mark he was born with, an expression of his cultural belonging, or a piece of fabric already placed on him to single him out and signal his loss of freedom.

A letter from July 31 is more telling of the boy’s familial background. We learn that his father was from Sasqua village, situated in the vicinity of the modern-day Fairfield, Connecticut.5 He did not fight against the English in what turned out to be the final battle against the Pequot, better known as the Fairfield Swamp Fight (July 14, 1637). Williams claims to have heard this from the boy’s mother (who scholars identify as Wincumbone). She, together with his two siblings, remained enslaved by John Winthrop. In his letter, Williams asks Winthrop to name the child before sending him his way and promises to “endeavour his good, and the common [good] in him.”6 After that, Williams’ letters do not reveal much about the boy’s life in his household.

Will was not the only Indigenous person held in the Williams’ household, although later records makes it difficult to distinguish between them at times. A document from 1663 mentions a “memorable storie of that yong Indian Prince or Sagemores sonne whom Mr Williams educated & over whom two of ther witches weere assured by the Devil they had noe power over him as long as hee was in his custodie.”7 It is difficult to say whether the boy with the red about his neck was indeed a child of that Pequot sachem. Either way, Williams’ willingness to properly raise the boy is in and of itself a deceitful euphemism. It represents the colonists’ views and hides the fact that the so-called education went hand in hand with the erasure of cultural and personal identity.8

Williams often relied on the Bible to justify his perspective, as did other colonists. They claimed that captives deserved either death or perpetual slavery. Indeed, this puritan’s readiness to enslave a child seems to have a more strategic background: He thought that enslavement of children and women would weaken Indigenous men.9

Although acquiring slaves was not the sole driving force behind the Pequot war, this story of the Pequot boy, albeit poorly documented, confirms that Indigenous slavery was not a peripheral issue in New England but a crucial component in the development of the northeastern colonies.

Further reading

Cave, Alfred A. The Pequot War. University of Massachusetts Press, 1996.

Keefer, Katrina H.B. “Marked by fire: brands, slavery, and identity.” A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies 40, no. 4 (May 7, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2019.1606521.

MacRury, Elizabeth Banks. This is Fairfield, 1639-1940: Pages from Three Hundred One Years of the Town’s Brilliant History. The Walker-Rackliff Company, 1960.

Morgan, Philip D. “Origins of American Slavery.” Magazine of History 19, no. 4 (July 2005): 2, https://www.proquest.com/docview/213743530?fromopenview=true&pq-origsite=gscholar&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals.

National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program Technical Report “Battle of Mystic Fort Documentation Plan” March 2009. http://pequotwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Technical-Report-Short.pdf Accessed December 6, 2024.

Newell, Margaret Ellen. Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery. Cornell University Press, 2015.

Williams, Roger, and Glenn W. LaFantasie. The Correspondence of Roger Williams. 2 vols. University Press of New England, 1988.

Footnotes

- Alfred A. Cave, The Pequot War (University of Massachusetts Press, 1996), 150–151.[↩]

- Roger Williams and Glenn W. LaFantasie, The Correspondence of Roger Williams, 2 vols. (University Press of New England), 1988, 2:89, note 3.[↩]

- Israel Stoughton to John Winthrop June 28, 1637, Winthrop Papers, 3:435–436.[↩]

- Roger Williams to John Winthrop, June 30, 1637, LaFantasie, 1:89n2.[↩]

- Roger Williams to John Winthrop, July 31, LaFantasie 1:109.[↩]

- Roger Williams to John Winthrop, July 31, LaFantasie 1:109.[↩]

- Petition from New England leaders to the English Crown, date unclear, but likely 1660s or 1670s. Ames, Eillis, and Robert C. Winthrop. “December Meeting. Visit of General Grant; Provincial Charter of Massachusetts; Colonial Papers; Letters from Charles J. Hoadly; Letter from Hugh Blair Grigsby; History of the Ordinance of 1787; Harvard-College Monitor’s Bill; Communication from Franklin B. Dexter.” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 10, 1867: 368–408. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25079390.[↩]

- Almost a year after the letter which references the boy’s family, Williams mentions “a native, mine own servant,” ca. 14 June 1638, LaFantasie, 1:163, and then, two weeks later, writes to Winthrop “This native, Will, my servant, shall attend your worship for answer.” ca. August 1; LaFantasie, 1:173. These isolated remarks have traditionally been used to suggest the Pequot boy and Will were the same person.[↩]

- Roger Williams to John Winthrop, July 31, LaFantasie 1:109.[↩]